Егор Холмогоров. «Ленинград — открытый город»

Дата: 27.01.2014 в 00:48

Рубрика : Публикации

Метки : 1941, вермахт, Вторая мировая война, Гитлер, Ленинград, право войны, Санкт-Петербург

Комментарии : 2 комментария

В связи со скандальной оптимистической выдачей известного оптимистического канала хотелось бы заметить несколько вещей.

1. Теоретически сдача городов под капитуляцию — объявление «открытых городов» во время Второй Мировой Войны практиковалась довольно часто. Брюссель и Париж-1940, Белград-1941, Манила-1942, Рим-1943, Афины-1944, Загреб-1945. Режим открытого города означал отказ от сопротивления в обмен на отказ от бомбежек, разрушения памятников, истребления гражданского населения. Разумеется, в каждом случае соблюдение режима открытого города полностью зависело от победившей стороны. Никаких обязывающих стороны конвенций о режиме подобных открытых городов не существовало.

2. На Восточном фронте этот режим не применялся ни одной из сторон ни разу — ни немцами, ни нами. При этом у немцев было несколько прекрасных случае объявить режим открытого города — это Будапешт в январе-феврале 1945 и Кенигсберг в апреле 1945, не говоря уж о Берлине. И там и там удалось бы избежать потерь мирного населения не менее 40 тысяч человек. Таким образом, вопрос о сдаче Ленинграда вряд ли рассматривался хотя бы одной из сторон конфликта.

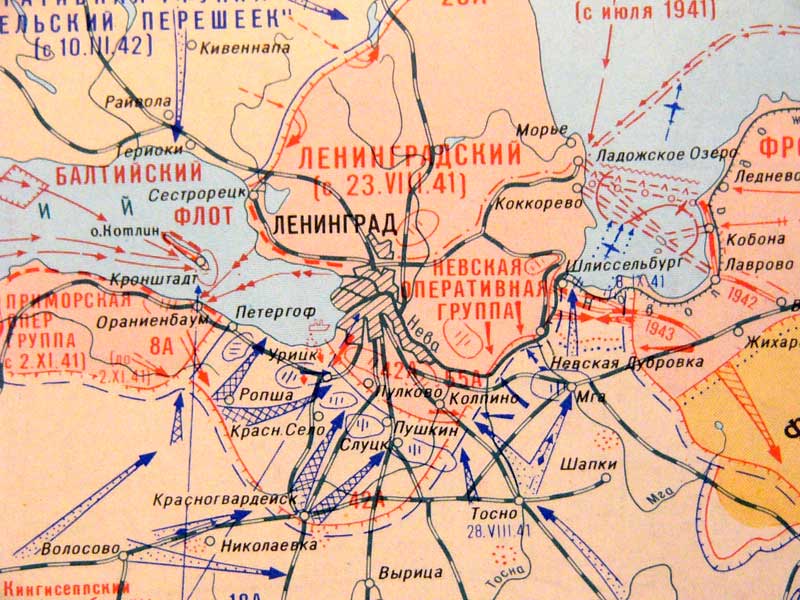

3. Стратегически такое явление как блокада Ленинграда могло быть просчитано — словосочетание «блокада Ленинграда» встречается еще в книге Эрнста Генри «Гитлер против СССР» опубликованной в 1937 (там подразумевалась однако блокада с моря английским флотом и с суши силами немецкого десанта), но оперативно блокада была внезапной, охват города наметился с 1 сентября, до 6 сентября 1941 немцы вели прямое наступление на город, и лишь когда наступление было остановлено по распоряжению Гитлера, немцы 8 сентября заняли Шлиссельбург и прервали коммуникации. До начала блокады из города вывезли 400 тыс человек, причем многие уезжать не хотели. Можно утверждать, что такое явление как блокада Ленинграда, а не его взятие были неожиданностью и для советского и для немецкого командования.

4. После взятия Ленинграда в блокаду вопросы гуманности, сохранения жизни населения немецким командованием всерьез не рассматривались. На эту тему существует множество немецких документов. Совсем циничные гитлерофилы пытались поставить это под сомнение, но их тут же заутюжили длинным списком документов из Федерального Военного Архива ФРГ. В цитате в конце данного текста — длинная подборка выписок из документов на немецком с переводами на английский. Во избежание утраты я её скопировал в полном объеме. Желающие могут изучать и переводить на русский.

Резюме этих документов дано в широко известной у нас директиве Германского ВМФ

Директива начальника штаба военно-морских сил Германии об уничтожении г. Ленинграда

22 сентября 1941 г.

г. Берлин

СекретноБудущее города Петербурга

1. Чтобы иметь ясность о мероприятиях военно-морского флота в случае захвата или сдачи Петербурга, начальником штаба военно-морских сил был поднят вопрос перед Верховным главнокомандованием вооруженных сил о дальнейших военных мерах против этого города.

Настоящим доводятся до сведения результаты.

2. Фюрер решил стереть город Петербург с лица земли. После поражения Советской России дальнейшее существование этого крупнейшего населенного пункта не представляет никакого интереса. Финляндия точно так же заявила о своей незаинтересованности в существовании этого города непосредственно у ее новых границ.

3.Прежние требования военно-морского флота о сохранении судостроительных, портовых и прочих сооружений, важных для военно-морского флота, известны Верховному главнокомандованию вооруженных сил, однако удовлетворение их не представляется возможным ввиду общей линии, принятой в отношении Петербурга.

4.Предполагается окружить город тесным кольцом и путем обстрела из артиллерии всех калибров и беспрерывной бомбежки с воздуха сравнять его с землей.

Если вследствие создавшегося в городе положения будут заявлены просьбы о сдаче, они будут отвергнуты, так как проблемы, связанные с пребыванием в городе населения и его продовольственным снабжением, не могут и не должны нами решаться. В этой войне, ведущейся за право на существование, мы не заинтересованы в сохранении хотя бы части населения.

5. Главное командование военно-морских сил в ближайшее время разработает и издаст директиву о связанных с предстоящим уничтожением Петербурга изменениях в уже проводимых или подготовленных организационных мероприятиях и мероприятиях по личному составу.

Если командование группы армий имеет по этому поводу какие-либо предложения, их следует как можно скорее направить в штаб военно-морских сил.

ГА РФ, ф. 7445, on. 2, д. 166, ял. 312-314, перевод с немецкого.

5. Как видим, постановка телеканалом «Дождь» вопроса о капитуляции Ленинграда как о способе сохранения его жителей объясняется исключительно их полным неведением подлинной обстановки на советско-германском фронте и в штабе немецкого главного командования в 1941 году.

6. За период с сентября 1941 по октябрь 1942 на «Большую землю» было эвакуировано 1 млн человек, несмотря на тяжелейшие транспортные условия. Таким образом, сравнение цифр эвакуации и позиции немецкого командования показывает, что продолжение обороны Ленинграда создавало более оптимальные условия для выживания конкретных его жителей, чем сдача города немцам.

7. То же можно сказать и о культурных ценностях. Абсолютное большинство культурных ценностей в Ленинграде не пострадало и не могло пострадать, поскольку налажены были меры по их маскировке, они были закрыты фанерой и обложены песком. Для сравнения дворцовые комплексы Петродворца и Павловска занятые немцами были уничтожены практически под ноль.

Резюме. Блокада Ленинграда стала как следствием грамотной обороны города, в результате которой не было допущено его взятие, так и следствием того, что Гитлер остановил наступательное продвижение ГА «Север» на Ленинград, затребовав у нее ударные танковые соединения. Предусмотреть заранее такую вещь как именно блокада, а не взятие города было нельзя. Сдача советскими войсками Ленинграда во избежание жертв среди мирного населения не могла быть осуществлена ни по условиям ведения войны на советско-германском фронте, ни в виду отсутствия у немецкого командования всякого намерения принимать подобную сдачу. Оборона города, в противоположность его взятию или сдаче, обеспечила не худшие, а лучшие шансы для выживания его жителей и обеспечила практически полную сохранность культурных памятников на незахваченной территории.

P.S. Приведу, также, предельно точное замечание Дмитрия Стешина.

К годовщине освобождения Ленинграда от Блокады на телеканале «Дождь» зрителям задали вопрос: «Нужно ли было сдать Ленинград, чтобы сберечь сотни тысяч жизней?».

Я много раз писал о людях страдающих редким, но заразным заболеванием: «педерастия мозга», то есть, мыслящих неконструктивно, имеющих иную парадигму сознания. Именно они поздравляли Микадо с победой в Цусимском сражении и принимали ордена от республики Ичкерия. Именно они сформулировали расхожий постулат: «если бы мы сдались немцам в 1941-ом, сейчас пили бы не «Жигулевское», а «Баварское». Хотя, судя по этническому составу «любителей баварского», скорее всего они бы не пиво пили немецкое, а существовали бы в качестве декоративных чехлов на комнатных осветительных приборах. И если бы Питер сдали бы немцам, было бы то же самое. Я объясню в нескольких словах.Взяв Ленинград, группа армий Север соединилась бы с финнами на реке Сестре, и в течение нескольких недель отрезала бы страну от незамерзающего порта Мурманск. Через этот порт мы получали сырье, химические компоненты, порох, взрывчатку, радиотехнические приборы, авиационный бензин. Дюраль, никель, оптику и боеприпасы – все то, что на первом этапе войны, пока не закончилась эвакуация предприятий на Урал, СССР не мог произвести или добыть в нужном количестве. И без чего невозможно было вести войну. В блокаде бы оказалась вся европейская часть страны – иранский транзит не смог бы обеспечить такого потока грузов. Связанные под городом немецкие войска были бы переброшены на другие участки фронта, в группу армий Центр, например, что закончилось бы падением Москвы. Или на юг – к бакинским приискам, где добывалась кровь войны — нефть.

Впрочем, сама война при таком раскладе закончилась бы уже в 1942 году. Благо в войну бы обязательно вступила затаившаяся Япония. Поспешила бы поучаствовать Испания, и прочие европейские союзники Гитлера. Вместо СССР получился бы Восточный протекторат, культурно поделенный между странами Оси. Фанатов баварского пива ждало бы страшное, фатальное разочарование не совместимое с жизнью. Таким образом, у них не народились бы детишки, и некому было бы создавать телеканал «Дождь», на нем работать и задавать публике скотские вопросы про Блокаду. Не сомневаюсь, что мои земляки сделают правильные выводы, и в культурной столице «Дождь» потеряет остатки своей аудитории.

Просто, в Ленинграде-Петербурге, следы блокады видны до сих пор. Это осколочные осыпи на гранитных набережных. Помороженные в блокаду старые зеркала, в которых до сих пор отражается кошмар тех 900 дней. Потолки, которые невозможно забелить даже через 70 лет – так въелась в них копоть от печек-буржуек. И хлеб, заплесневелый хлеб, который невозможно выкинуть в мусорное ведро – физически чувствуешь, как отсыхают твои руки. Эта неосознанная реакция – дань нашим предкам, которые в отличие от телеканала «Дождь», знали, за что умирали. Не за дворцы и набережные, не за картины и скульптуры – за нас. У них был подлый выбор, но они его не сделали.

Как говорится, — ни прибавить, ни убавить…

Цитата:

Potyondi

The Siege of Leningrad in German DocumentsTo begin, I shall post but 3 of the documents and follow up with more later. All quotes, except where otherwise indicated, were taken from the catalogue of the current exhibition Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941-1944. Dimensionen des Vernichtungskrieges.

1. From the personal war diary of Generaloberst Franz Halder, entry of 08.07.1941 (Generaloberst Halder, Kriegstagebuch, Bd. III: Der Rußlandfeldzug bis zum Marsch auf Stalingrad (22.6.1941 -24.9.1942), bearb. von Hans-Adolf Jacobsen, Stuttgart 1964, page 53)

Quote:

[…] 8.7.1941: Ergebnis […]2. Feststehender Beschluß des Führers ist, Moskau und Leningrad dem Erdboden gleich zu machen, um zu verhindern, daß Menschen darin bleiben, die wir dann im Winter ernähren müßten. Die Städte sollen durch die Luftwaffe vernichtet werden. Panzer dürfen hierfür nicht eingesetzt werden. […]

Translation:Quote:

[…] 8.7.1941: Result […]2. It is the established decision of the Führer to erase Moscow and Leningrad in order to avoid that people stay in there who we will then have to feed in winter. The cities are to be destroyed by the air force. Tanks may not be used for this purpose. […]

2. Order of the Army High Command (Oberkommando des Heeres) to Army Group North of 28.09.1941 (Bundersarchiv/Militärarchiv, RM 7/1014)

Quote:

Betrifft: Abschließung der Stadt LeningradAn

Heeresgruppe Nord

Auf Grund der Weisung der Obersten Führung wird befohlen:

1.) Die Stadt Leningrad ist durch einen möglichst nahe an die Stadt heranzuschiebenden und dadurch Kräfte sparenden Ring einzuschliessen. Eine Kapitulation ist nicht zu fordern.

2.) Um zu erreichen, dass die Stadt als Zentrum des letzten roten Widerstandes an der Ostsee möglichst bald ausgeschaltet wird, ohne dass grössere eigene Blutopfer gebracht werden, ist die Stadt infanteristisch nicht anzugreifen. Sie ist vielmehr durch Niederkämpfen der Luftabwehr und der feindlichen Jäger, durch Zerstörung der Wasserwerke, Lagerhäuser, Licht- und Kraftquellen ihrer Lebens- und Verteidigungsfähigkeit zu berauben. Die militärischen Anlagen und Verteidigungskräfte des Gegners sind durch Feuer und Beschuss niederzukämpfen. Jedes Ausweichen der Zivilbevölkerung gegen die Einschliessungstruppen ist — wenn nötig unter Waffeneinsatz — zu verhindern.

3.) Durch Verbindungsstab Nord wird bei Finnischem Oberkommando gefordert werden, dass die in der Karelischen Landenge vorgehenden finnischen Kräfte die Einschliessung Leningrads von Norden und Nordosten her im Anschluss an die über die Newa vorgehenden deutschen Kräfte übernehmen und dass die Einschliessung selbst nach obigen Gesichtspunkten erfolgt.Umgehende Verbindungsaufnahme zwischen Heeresgruppe Nord und Verbindungsstab Nord wegen Regelung der Einzelheiten wird von OKH zeitgerecht befohlen.

I.A.

gez. Halder

Translation:Quote:

Subject: Sealing off the city of LeningradTo

Army Group North

According to directives of the Supreme Command the following is ordered:

1.) The city of Leningrad is to be sealed of by a ring to be taken as close as possible to the city in order to save forces. A capitulation is not to be required.

2.) In order to achieve that the city as center of the last great Red resistance on the Baltic is eliminated as soon as possible without greater sacrifices in blood of our own being brought, the city is not to be attacked by infantry. It is to be deprived of its life and defense capacity by crushing the enemy air defense and fighter planes and destroying waterworks, stores and sources of light and power. The military installations and defense forces of the enemy are to be crushed by fire and bombardment. Any move by the civilian population in the direction of the encircling troops is to be prevented – if necessary by force of arms.

3.) Liaison Staff North will require the Finnish high command to provide for the Finnish troops advancing in the Karelian isthmus taking over the encirclement from the north and north-east in connection with the German troops advancing over the Neva and the encirclement itself being carried out according to the above criteria.Immediate contact between Army Group North and Liaison Staff North for regulation of details will be ordered by Army Supreme Command in due time.

By order

signed Halder

3. From the letter of General Quarter Master Eduard Wagner to his wife of 09.09.1941 (Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv, N 510/48 )

Quote:

[…] Der Nordkriegsschauplatz ist so gut wie bereinigt, auch wenn man nichts davon hört. Zunächst muß man sie in Petersburg schmoren lassen, was sollen wir mit einer 3 ½ Mill-Stadt, die sich nur auf unser Verpflegungsportemonnaie legt. Sentimentalitäten gibt’s dabei nicht […]

Translation:Quote:

[…] The northern theater of war is a good as cleaned up, even if you hear nothing about it. Now we first must let them fry in Petersburg, what are we to do with a city of 3 ½ million that would only lie on our food supply wallet. Sentimentalities there will be none. […]07-31-2004, 02:58 AM

Potyondi4. Lecture note from the Wehrmacht Command Staff at the Wehrmacht High Command about possible variants of the siege of Leningrad, 21.9.1941 (Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv, RW 4/v.578, Bl. 144-146)

Quote:

Vortragsnotiz LeningradMöglichkeiten:

1.) Stadt besetzen, also so verfahren, wie wir es mit anderen russischen Großstädten gemacht haben:

Abzulehnen, weil uns dann die Verantwortung für die Ernährung zufiele.

2.) Stadt eng abschliessen, möglichst mit einem elektrisch geladenen Zaum umgeben, der mit M.Gs. bewacht wird.

Nachteile: Von etwa 2 Millionen Menschen werden die Schwachen in absehbarer Zeit verhungern, die Starken sich dagegen alle Lebensmittel sichern und leben bleiben. Gefahr von Epidemien, die auf unsere Front übergreifen. Ausserdem fraglich, ob man unseren Soldaten zumuten kann, auf ausbrechende Frauen und Kinder zu schiessen.

3.) Frauen, Kinder, alte Leute durch Pforten des Einschliessungsringes abziehen, Rest verhungern lassen:

a) Abschieben über den Wolchow hinter die feindliche Front theoretisch gute Lösung, praktisch aber kaum durchführbar. Wer soll Hunderttausende zusammenhalten und vorwärtstreiben? Wo ist dann die russische Front?

b) Verzichtet man auf den Abmarsch hinter die russische Front, verteilen sich die Herausgelassenen über das Land.

Auf alle Fälle bleibt Nachteil bestehen, dass die verhungernde Restbevölkerung Leningrads einen Herd für Epidemien bildet und dass die Stärksten noch lange in der Stadt bleiben.

4.) Nach Vorrücken der Finnen und vollzogener Abschliessung der Stadt wieder hinter die Newa zurückgehen und das Gebiet nördlich dieses Abschnitts den Finnen überlassen.

Finnen haben inoffiziell erklärt, sie würden Newa gern als Landesgrenze haben, Leningrad müsse aber weg. Als politische Lösung gut. Frage der Bevölkerung Leningrads aber nicht durch Finnen zu lösen. Das müssen wir tun.

Ergebnis und Vorschlag

Befriedigende Lösung gibt es nicht. H.Gr. Nord muss aber, wenn es so weit ist, einen Befehl bekommen, der wirklich durchführbar ist.

Es wird vorgeschlagen:

a) Wir stellen vor der Welt fest, dass Stalin Leningrad als Festung verteidigt. Wir sind also gezwungen, die Stadt mit ihrer Gesamtbevölkerung als militärisches Objekt zu behandeln. Trotzdem tun wir ein Übriges: Wir gestatten dem Menschenfreund Roosevelt, nach einer Kapitulation Leningrad die nicht in Kriegsgefangenschaft gehenden Bewohner unter Aufsicht des Roten Kreuzes auf neutralen Schiffen mit Lebensmitteln zu versorgen oder in seinen Erdteil abzubefördern und sagen für diese Schiffsbewegung freies Geleit zu (Angebot kann selbstverständlich nicht angenommen werden, nur propagandistisch zu werten).

b) Wir schliessen Leningrad zunächst hermetisch ab und schlagen die Stadt, soweit mit Artillerie und Fliegern möglich, zusammen (vorerst nur schwache Fliegerkräfte verfügbar!).

c) Ist die Stadt dann durch Terror und beginnenden Hunger reif, werden einzelne Pforten geöffnet und Wehrlose herausgelassen. Soweit möglich, Abschub ins innere Russland, Rest wird sich zwangsläufig über das Land verteilen.

d) Rest der «Festungsbesatzung» wird den Winter über sich selbst überlassen. Im Frühjahr dringen wir dann in die Stadt ein (wenn die Finnen es vorher tun, ist nichts einzuwenden), führen das, was noch lebt, nach Innerrussland bzw. in die Gefangenschaft, machen Leningrad durch Sprengungen dem Erdboden gleich und übergeben den Raum nördlich der Newa den Finnen.

Translation:Quote:

Lecture Note LeningradPossibilities:

1.) Occupy the city, i.e. proceed as we have in regard to other Russian big cities:

To be rejected because we would then be responsible for the feeding.

2.) Seal off city tightly, if possible with an electrified fence guarded by machine guns.

Disadvantages: Of about 2 million people the weak will starve to death within a foreseeable time, whereas the strong will secure all food supplies and stay alive. The danger of epidemics that carry over to our front. It is also questionable whether our soldiers can be burdened with having to shoot on women and children trying to break out.

3.) Take out women, children and elder men through gates in the encirclement ring, let the rest starve to death:

a) Removal across the Volchov behind the enemy front theoretically a good solution, but can hardly be carried out in practice. Who is to keep hundreds of thousands together and drive them on? Where is the Russian front in this case?

b) If we do without a march behind the Russian front, those let out will spread across the land.

At any rate there remains the disadvantage that the starving remaining population of Leningrad constitutes a source of epidemics and that the strongest still remain in the city for a long time.

4.) After advance of the Fins and concluded sealing off of the city, we go back behind the Neva and leave the area to the north of this section to the Fins.

The Fins have unofficially declared, that they would like to have the Neva as their country’s border, but that Leningrad must go. Good as a political solution. The question of the population is not to be solved by the Fins, however. This we have to do.

Result and suggestion:

There is no satisfactory solution. Army Group North must, however, receive an order that can actually be carried out when the time comes.

The following is suggested:

a) We determine before the world that Stalin is defending Leningrad as a fortress. We are thus forced to treat the city with its entire population as a military objective. We nevertheless do more: We allow the humanitarian Roosevelt to feed the inhabitants not becoming prisoners of war after a capitulation of Leningrad under the supervision of the Red Cross or to transport them to his continent and guarantee free escort for this shipping movement (the offer can of course not be accepted, it is to be seen merely under propaganda aspects).

b) We seal off Leningrad hermetically for the time being and crush the city, as far as possible, with artillery and air power (only weak aerial forces available at the time!).

c) As soon as the city is ripe through terror and beginning hunger, a few gates are opened and the defenseless are let out. Insofar as possible they will be pushed of to inner Russia, the rest will necessarily spread across the land.

d) The rest of the «fortress defenders» will be left to themselves over the winter. In spring we then enter the city (if the Fins do it before us we do not object), lead those still alive to inner Russia or into captivity, wipe Leningrad from the face of the earth through demolitions and then hand over the area north of the Neva to the Fins.

5. Letter of the Navy Liaison Officer at Army Group North of 22.9.1941 (Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv, RM 7/1014, Bl. 39-41)

Quote:

Sehr verehrter Herr Admiral,ich schreibe Ihnen wegen des Schicksals von Leningrad, welches jetzt der Entscheidung entgegengeht. Als ich am 19. dem Grossadmiral in Reval Vortrag hielt, war ihm offenbar unbekannt, dass es nicht beabsichtigt ist, in die Stadt hineinzugehen. Bei der Eroberung von Warschau haben wir damit böse Erfahrungen gemacht. Das weitere Vorgehen hatte sich der Führer, als er vor etwa 8 Wochen die Heeresgruppe besuchte, persönlich vorbehalten.

Ich habe aus gewissen Andeutungen, die mir der hiesige Chef des Generalstabes machte, den Eindruck, dass die Entscheidung etwa in folgendem Sinne nunmehr gefallen ist:

Leningrad ist die Geburtsstätte des Bolschwismus. Solange sie in deutscher Hand ist, wird sie dieselbe Rolle spielen, wie Konstantinopel für das zaristische Russland. Ihre Rückeroberung wird Programmpunkt Nr. 1 für den Bolschewismus sein, den der Führer in den asiatischen Raum zurückdrängen will. Die Stadt muss daher vom Erdboden verschwinden, wie s. Zt. Karthago.

Auch aus raumpolitischen Gründen ist dies erforderlich, da die Newa die Grenze zwischen Finnland und Ostland werden soll.

Zudem ist es klar, dass wir die Einwohner, z.Zt. auf etwa 5 Millionen geschätzt, nicht ernähren können.

Vermutlich soll die Stadt durch Artillerie, Bomben, Feuer, Hunger und Kälte vernichtet werden, ohne dass ein deutscher Soldat ihren Boden betritt.

Ich persönlich möchte bezweifeln, dass das bei der unglaublichen Zähigkeit des russischen Menschen gelingt. M.E. lassen sich nicht 4 — 5 Millionen Menschen so einfach umbringen.

Ich habe das aus eigener Anschauung in Kowno gesehen, wo die Letten

6 000 Juden erschossen haben, darunter Frauen und Kinder. Selbst ein so rohes Volk wie die Letten konnten dieses Morden schliesslich nicht mehr mit ansehen. Die ganze Aktion verlief dann im Sande. Wieviel schwieriger wird das mit einer Millionenstadt sein.

Zudem würde das m.E. einen Entrüstungssturm in der ganzen Welt auslösen, den wir uns politisch nicht leisten können.

Ich schneide diese Fragen an, da sie marine — politisch von grosser Bedeutung sind.

Als Hafen ist Leningrad ohne Zweifel ein Gewaltlösung, die Peter der Grosse zwangsweise wählen musste. Für das kommende Ostland wird der eisfreie Hafen von Reval oder Baltischport das Einfallstor zur See sein. Vielleicht kommt noch als Sommerhafen ein weiter ostwärts gelegener Hafen, z.B. Ust-Luga oder Oranienbaum in Frage.

Betreten wir Leningrad nicht, so bleibt der Marine die Ingangsetzung der Werften versagt. Es bleibt die Frage offen, ob wir uns das bei dem noch bevorstehenden Endkampf gegen England — U.S.A. leisten können. Schliesslich kann Leningrad auch später verschwinden, wenn wir den Seekrieg gewonnen haben.

Ich denke mir folgende Lösung: Wir erklären, dass wir wegen der Blockade durch England nicht in der Lage sind, die Bevölkerung dieser Riesenstadt noch zusätzlich zu ernähren. Zumal in einem Lande, dessen Ernährungsbasis durch die bolschewistische Misswirtschaft so verkommen ist. Wir gestatten den Frauen, Kindern und alten Männern freien Abzug. England und U.S.A. können Schiffe schicken, um sie an einen anderen Ort der Welt nach freier Wahl zu fahren. Die wehr- und arbeitsfähigen Männer kommen in Gefangenschaft.

Lehnt England / U.S.A. das Angebot ab, so tragen sie vor der Weltöffentlichkeit die Schuld am Untergang dieser Menschen. Nehmen sie es an, so sind wir die Sorge los und ihnen kostet es erheblichen Frachtraum.

Wir nehmen nach der Kapitulation gleichzeitig die Werften und einige wenige Versorgungsbetriebe mit Kriegsgefangenen in Betrieb und bauen dort ohne Luftgefährdung die Flotte, die wir für den Endkampf brauchen.

Währenddessen kann die Evakuierung der Stadt und ihr Abbau beginnen. Ist der Krieg siegreich beendet, verschwinden die noch verbliebenen Reste der Stadt. Die Werften werden nach Reval oder Baltisch Port verlegt.

Ich habe hier den Eindruck, dass im engsten Kreise um den Führer der Entschluss, wie gegen die Stadt vorgegangen wird, seit etwa 14 Tagen vorliegt, aber die verschiedensten Kreise aus bestimmten Gründen nicht unterrichtet werden.

Ich unterrichte Sie hierüber der Eile wegen unmittelbar. Vielleicht ist meine Sorge unnötig und die Seekriegsleitung genau im Bilde. Ich hielt es jedenfalls für meine Pflicht, meine Marinevorgesetzten über die hier gewonnenen Eindrücke zu unterrichten. Ich wäre dankbar, wenn die ganze Angelegenheit entsprechend vertraulich behandelt wird.

Da das taktische Vorgehen gegen die russische Flotte, Kronstadt und Leningrad in hohem Masse von den Endabsichten abhängig ist, wäre ich für eine kurze Unterrichtung dankbar. Dies ist erforderlich, da ich nur so meinen Oberbefehlshaber, der sehr viel Verständnis für die Marine und die Gesamtkriegsführung hat, sachlich richtig beraten kann. Fällt die Entscheidung gegen die Marine, so können viele Bindungen fortfallen, wie z.B, das Schonen der Werften und Hafenanlagen. Das würde den ohnehin sehr blutigen Kampf erleichtern. Auch Kronstadt braucht dann nicht genommen zu werden.Mit ergebensten Grüssen

und Heil Hitler

Ihr

[Unterschrift]

Kapitän zur See

Translation:Quote:

Most Honored Admiral,I’m writing to you because of the fate of Leningrad, which is now approaching decision. When I held a lecture to the Grand Admiral in Reval on the 19th, he obviously did not know that it is not intended to enter the city. During the conquest of Warsaw we had bad experiences with this. The further procedure the Führer reserved to himself personally when he visited the Army Group about 8 weeks ago.

From several hints given to me by the local head of general staff I got the impression that the decision has by now been taken in about the following sense:

Leningrad is the birthplace of Bolshevism. As long as it is in German hands it will have the same role that Constantinople used to have for the Czars’ Russia. Its re-conquest will be point no. 1 on the program of Bolshevism, which the Führer wants to displace into Asia. The city must thus disappear from the face of the earth, like Cartage in its time.

Also for reasons of territorial policy this is necessary, because the Neva is to become the new frontier between Finland and the Eastern Territories.

Besides it is clear than we cannot feed the inhabitants, which are currently estimated at about 5 million.

The city is presumably to be destroyed by artillery, bombs, fire, hunger and cold, without a single German soldier stepping into it.

I personally doubt that this will be possible, given the incredible toughness of the Russian. In my opinion 4 to 5 million people cannot be killed off that easily.

I saw this with my own eyes in Kovno, where the Latvians shot 6 000 Jews, among them women and children. Even a people as rude as the Latvians could no longer bear the sight of this murder in the end. The whole action then ran out of steam. How much more difficult will this be with a city of millions.

Besides this would in my opinion lead to a storm of indignation in the whole world, which we politically cannot afford.

I address these questions because they are of great importance in terms of naval policies.

As a port Leningrad is without doubt a makeshift solution that Peter the Great had to choose. For the future Eastern Territories the ice-free harbor of Reval or Baltischport will be the gateway to the sea. Maybe a port further to the East, e.g. Ust-Luga or Oranienbaum, is to be considered additionally as a summer port.

If we don’t set foot in Leningrad, our navy is kept from putting the threws to function. The question is whether we can afford this in view of the final fight against England and the U.S.A. still in front of us. After all Leningrad can also disappear at a later stage, when we have won the war at sea.

I imagine the following solution: We declare that due to the blockade by England we are not in conditions to additionally feed the population of this giant city. This especially in a land the food basis of which is so deteriorated due to Bolshevik mismanagement. We allow the women, children and old men to leave at will. England and the U.S.A. may send ships to taken them to another part of the world at their choice. The men able to fight and to work will be taken into captivity.

If England / U.S.A. refuse this proposal, they bear the responsibility for the demise of these people before world opinion. If they accept, we are rid of the problem and they have to expend additional freight room.

After the capitulation we immediately start operating the threws and some supply installations with prisoners of war and without danger from the air build the fleet that we need for the final fight.

In the meantime the evacuation and deconstruction of the city may commence. Once the war has been victoriously concluded, what still remains of the city will disappear. The threws will be taken to Reval or Baltisch Port.

I have the impression that in the closest circle around the Führer the decision how to proceed against the city has been taken about 14 days ago but the most varied circles are not informed thereof for certain reasons.

I inform you hereof directly due to the urgency of the matter. Maybe my concern is unnecessary and the Naval Command is accurately informed. At any rate I considered it my duty to inform my navy superiors about the impressions gained here. I would be grateful if the whole matter could accordingly be treated confidentially.

As the tactical proceeding against the Russian fleet, Kronstadt and Leningrad depends to a great extent on the final intentions, I would be very grateful for a brief notice. This is necessary because only thus I will be able to provide accurate counsel in the matter to my supreme commander, who has much understanding for the navy and the overall conduct of the war. If the decision is taken against the navy, many constraints can be eliminated, like for instance the sparing of the thews and port installations. This would make the anyway very bloody fighting easier. Neither would Kronstadt have to be taken in this case.With my most submissive regards

and Heil Hitler

Yours truly,

[signature]

Captain at See

6. The Führer’s Decision on Leningrad (Entschluß der Führers über Leningrad), transmitted by the Naval Warfare Command (Seekriegsleitung) to Army Group North on 29.09.1941 (Tagebuch der Seekriegsleitung, quoted in Max Domarus, Hitler Reden und Proklamationen 1932-1945, Volume 4, Page 1755)

Quote:

Betrifft: Zukunft der Stadt Petersburg

II. Der Führer ist entschlossen, die Stadt Petersburg vom Erdboden verschwinden zu lassen. Es besteht nach der Niederwerfung Sowjetrußlands keinerlei Interesse an dem Fortbestand dieser Großsiedlung. Auch Finnland hat gleicherweise kein Interesse an dem Weiterbestehen der Stadt unmittelbar an seiner neuen Grenze bekundet.

III. Es ist beabsichtigt, die Stadt eng einzuschließen und durch Beschuß mit Artillerie aller Kaliber und laufendem Laufeinsatz dem Erdboden gleichzumachen.

IV. Sich aus der Lage der Stadt ergebende Bitten um Übergabe werden abgeschlagen werden, da das Problem des Verbleibens und der Ernährung der Bevölkerung von uns nicht gelöst werden kann und soll. Ein Interesse an der Erhaltung auch nur eines Teils dieser großstädtischen Bevölkerung besteht in diesem Existenzkrieg unsererseits nicht. Notfalls soll gewaltsame Abschiebung in den östlichen russischen Raum erfolgen.

Translation:Quote:

Subject: Future of the City of Petersburg

II. The Führer is determined to remove the city of Petersburg from the face of the earth. After the defeat of Soviet Russia there can be no interest in the continued existence of this large urban area. Finland has likewise manifested no interest in the maintenance of the city immediately at its new border.

III. It is intended to encircle the city and level it to the ground by means of artillery bombardment using every caliber of weapon, and continual air bombardment.

IV. Requests for surrender resulting from the city’s encirclement will be denied, since the problem of relocating and feeding the population cannot and should not be solved by us. In this war for our very existence, there can be no interest on our part in maintaining even a part of this large urban population. If necessary forcible removal to the eastern Russian area is to be carried out.

More is to follow.07-31-2004, 08:14 AM

Von ApfelstrudelWhoa, that «Zukunft der Stadt Petersburg» statement is really scary …

08-01-2004, 08:13 AM

Cd.Interesting stuff. The Nazis were certainly no friends to the Russian people.

I would add that the citizens of Leningrad were in such a desperate situation that for a while many resorted to cannibalism.

After the seige was lifted many people in Leningrad were arrested and sent away for collaboration with the enemy even though there was no evidence of this because it was thought that it was impossible for people to survive without some form of illicit trade with the enemy. It was all bogus but Stalin used it as a way to weed out his enemies within the city.

Rather sad reality for the Russian people is they had two enemies during the war, Hitler and Stalin.

08-10-2004, 07:05 AM

Potyondi7. Order of the Wehrmacht Supreme Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) to the Army Supreme Commander (Oberbefehlshaber des Heeres) about the rejection of capitulation offers from Leningrad or Moscow, 7.10.1941 (Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv, RM; 7/1014, Bl. 51 f.)

Quote:

Der Führer hat erneut entschieden, dass eine Kapitulation von Leningrad oder später von Moskau nicht anzunehmen ist, auch wenn sie von der Gegenseite angeboten würde.

Die moralische Berechtigung zu dieser Maßnahme liegt vor aller Welt klar. Ebenso wie in Kiew durch Sprengungen mit Zeitzündern die schwersten Gefahren für die Truppe entstanden sind, muß damit in Moskau und Leningrad in noch stärkerem Maße gerechnet werden. Dass Leningrad unterminiert sei und bis zum letzten Mann verteidigt würde, hat der sowjetrussische Rundfunk selbst bekannt gegeben.

Schwere Seuchengefahren sind zu erwarten.

Kein deutscher Soldat hat daher diese Städte zu betreten. Wer die Stadt gegen unsere Linien verlassen will, ist durch Feuer zurückzuweisen. Kleinere, nicht gesperrte Lücken, die ein Herausströmen der Bevölkerung nach Innerrußland ermöglichen, sind daher nur zu begrüßen. Auch für die übrigen Städte gilt, dass sie vor der Einnahme durch Artilleriefeuer und Luftangriffe zu zermürben sind und die Bevölkerung zur Flucht zu veranlassen ist.

Das Leben deutscher Soldaten für die Errettung russischer Städte vor einer Feuergefahr einzusetzten oder deren Bevölkerung auf Kosten der deutschen Heimat zu ernähren, ist nicht zu verantworten.

Das Chaos in Rußland wird umso größer, unsere Verwaltung und Ausnützung der besetzten Ostgebiete umso leichter werden, je mehr die Bevölkerung der sowjetrussischen Städte nach dem Innern Rußlands flüchtet.

Dieser Wille des Führers muß sämtlichen Kommandeuren zur Kenntnis gebracht werden.Der Chef des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht

I.A.

gez. Jodl

Translation:Quote:

The Führer has decided anew that a capitulation of Leningrad or later of Moscow is not to be accepted even if it were to be offered by the enemy.

The moral justification for this measure lies clear before all the world. Just like in Kiev explosions with time fuses caused the greatest dangers for the troops, the same must be counted on in Moscow and Leningrad to an even greater extent. The Soviet radio itself has informed that Leningrad is sewn with mines and will be defended to the last man.

A severe risk of epidemics is to be expected.

No German soldier may thus set foot in these cities. Whoever wants to leave the city in the direction of our lines is to be rejected by fire. Smaller gaps not sealed which allow for a streaming out of the population to inner Russia are thus only to be welcomed. Also for the other cities the principle applies that prior to being taken they must be worn down by artillery fire and air attacks and the population induced into fleeing them.

It is not supportable to risk the lives of German soldiers for the salvation of Russian cities from the danger of fire or to feed their population at the expense of the German homeland.

The chaos in Russia will be all the greater, our administration and exploitation of the occupied Eastern territories will be all the easier, the more the population of the Soviet Russian cities flees to inner Russia.

This will of the Führer all commanders must be notified of.The Head of the Wehrmacht High Command

By order

signed. Jodl

8. Report of the Head of the General Staff of Army Group North about a front line trip to the 18th Army, war diary of Army Group North, 24.10.1941 (Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv, RH 19III/168)Quote:

Ia fährt in den Bereich der 18. Armee.

Aktennotiz über die Fahrt des 1. Genst.Offz. am 24.10. in den Bereich der 18. Armee.

1.) Es wurden aufgesucht:

a) Gen.Kdo. L. A.K. (Krasnogwardeisk),

b) Artl.-B-Stelle auf Höhe 112 hart ostw. Krasnoje Sjelo.

c) Sicherungen an der Kronstädter Bucht Strjelna, Uritzk (A.A. 212),

d) Stab 58. I.D.,

e) OAK 18

2.) Bei allen aufgesuchten Stellen wurde die Frage aufgeworfen,. wie man sich zu verhalten hat, wenn die Stadt Leningrad ihre Übergabe anbietet und wie man sich gegenüber der aus der Stadt herausströmenden Bevölkerung verhalten soll. Es entstand der Eindruck, daß die Truppe vor diesem Augenblick große Sorgen hat. Der Kdr. der 58. I.D. betonte, daß er in seiner Div. den Befehl gegeben hat, den er auch von höherer Stelle erhielt und der den gegebenen Anweisungen entspricht, daß auf derartige Ansprüche zu schießen ist, um sie gleich im Keime zu ersticken. Er war der Ansicht, daß die Truppe diesen Befehl auch ausführen wird. Ob sie aber die Nerven behält, bei wiederholten Ausbrüchen immer wieder auf Frauen und Kinder und wehrlose alte Männer zu schießen, bezweifelte er. Bemerkenswert ist seine Äußerung, daß er vor der militärischen Gesamtlage, die gerade bei seinem Flügel bei Uritzk immer gespannt sei, keine Angst habe, daß aber die Lage gegenüber der Zivilbevölkerung immer Angst verursache. Dies sei nicht nur bei ihm, sondern bis zur Truppe herunter der Fall. In der Truppe bestehe volles Versändnis dafür, daß die Millionen Menschen, die in Leningrad eingeschlossen seien, von uns nicht ernährt werden können, ohne daß sich dies auf die Ernährung im eigenen Land nachteilig auswirkt. Aus diesem Grunde würde der deutsche Soldat auch mit Anwendung der Waffe derartige Ansprüche verhindern. Nur zu leicht könne das aber dazu führen, daß der deutsche Soldat dadurch seine innere Haltung verliert, d.h. daß er auch nach dem Kriege vor derartigen Gewalttätigkeiten nicht mehr zurückschrecke.

Führung und Truppe bemühen sich eifrig, eine andere Lösung dieser Frage zu finden, haben aber bisher noch keinen brauchbaren Weg gefunden.3.) Das Kampfgebiet, sowohl am Einschließungsring von Leningrad, wie auch im Küstengebiet südl. Kronstadt wird z.Zt. von der dort noch wohnenden Zivilbevölkerung evakuiert. Dies ist notwendig, da diese Zivilbevölkerung dort nicht mehr ernährt werden kann. Der Abschub erfolgt korpsweise so, daß die Zivilbevökerung in das rückw. Heeresgebiet gebracht und dort auf die Bauerndörfer verteilt wird. Unbeschadet dessen hat sich ein großer Teil der Zivilbevölkerung selbständig auf den Weg nach Süden gemacht, um sich neue Unterkunft und Lebensmöglichkeiten zu suchen. Entlang der großen Straße Krasgnowardeisk, Pleskau läuft z.Zt. eine Flüchtlingsbewegung von mehreren Tausend Menschen, in der Hauptsache nur Frauen, Kinder und alte Männer. Wo diese hinziehen, wie sie sich ernähren, ist nicht festzustellen. Es besteht der Eindruck, daß diese Menschen über kurz oder lang dem Hungertode verfallen müssen. Auch dieses Bild wirkt sich auf den deutschen Soldaten, der an dieser Straße zu Bauarbeiten eingesetzt ist, nachteilig aus.

A.O.K. 18 hat darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß z.Zt. nach Leningrad immer noch Flugblätter hereingeworfen werden, die zum überlaufen auffordern. Das steht nicht im Einklang mit der Weisung, daß Überläufer nicht angenommen werden. Zunächst werden Überläufer, die Soldaten sind (das sind täglich rund 100 — 120 Mann), noch angenommen. Eine Änderung der Flugblattpropaganda soll aber eintreten.

Translation:Quote:

Ia travels to the area of the 18th Army.

File note on the trip of the 1st General Staff Offices on 24.10. into the area of the 18th Army.

1.) The following were visited:

a) General Command L Army Corps (Krasnogwardeisk),

b) Artillery observation post on height 112 hard to the east of Krasnoje Sjelo.

c) Security posts on the Kronstadt Bay Strjelna, Uritzk (A.A. 212),

d) Staff of the 58th Infantry Division

e) Army High Command 18

2.) At all visited entities the question was addressed how to behave if the city of Leningrad should offer its surrender and how to behave in regard to the population streaming out of the city. The impression arose that the troops have the highest concerns in regard to this moment. The commander of the 58th Infantry Division pointed out that in his division he had given the order received from higher above, which corresponds to the instructions issued that such pretensions are to be fired on so as to strangle them at birth. He was of the opinion that the troops would also carry out this order. He doubted, however, whether they would keep the nerve to shoot again and again on women and children and defenseless elder men in case of repeated breakouts. It is worth noticing his utterance that he was not afraid of the military situation on the whole, which especially at his wing near Uritzk is always tense, but that the situation in regard to the civilian population always caused fear. This, he said, was not the case only with him, but also down to troop level. The troops fully understood that the millions of people encircled in Leningrad could not be fed by us without this having a negative impact on the food situation in our own country. For this reason the German soldier would also prevent such pretensions by force of arms. This, however, could only too easily lead to the German soldier losing his inner posture, i.e. not shying from such acts of violence even after the war.

The commanders and troops are eagerly trying to find another solution but have not found a plausible one so far.3.) The combat area, both at the encirclement ring of Leningrad and in the coastal area to the south of Kronstadt, is currently being evacuated of the civilian population still living there. This is necessary because the civilian population can no longer be fed there. The removal is carried out by each army corps in such a way that the civilian population is taken to the army rear area and there spread throughout the peasant villages. Nevertheless a great part of the civilian population has departed for the south on its own in order to find new shelter and means of subsistence. Along the great street of Krasgnowardeisk, Pleskau there is at the time a refugee movement of several thousand people, mainly consisting only of women, children and old men. Where these are going and how they feed themselves cannot be established. There is the impression that these people must in the short or long run die of starvation. This image also has a negative influence on the German soldiers used at this road for construction work.

Army High Command 18 has pointed out that at this time leaflets calling for defection are still being thrown into Leningrad. This is not in accordance with the instruction that defectors will not be accepted. For the time being defectors who are soldiers (those amount to around 100 – 120 men a day) are still accepted. However, a change of the leaflet propaganda is to occur.9. From the War Diary of the General Command of L. Army Corps, 18.9.1941 — 6.5.1942 (Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv, RH 24/5015)

Quote:

24.10.1941

Der Kdr. General besuchte eine Reihe Feuerstellungen schwerer und leichter Batterien des A.R. 269. Der Krd. General besichtigte die Einrichtungen für den Winter und den Stellungsbau uind besprach dann mit den Kommandeuren und Batteriechefs den Einsatz der Artillerie für den Fall, dass die russ. Zivilbevölkerung Ausbruchsversuche aus Leningrad machen sollte. Ein solches Herausdrängen ist laut Armeebefehl vom 18.9.1941 Nr. 2737/41 geh. notfalls mit Waffengewalt zu verhindern. Es ist Aufgabe der Artillerie, durch frühzeitige Feuereröffnung jedes derartige Unternehmen möglichst weit vor der eigenen Linie abzuweisen, damit es der Infanterie möglichst erspart bleibt, auf Zivilisten zu schiessen.

In gleicher Weise waren bei den Truppenbesuchen in den letzten Tagen die Art.-Regimenter der SS-Pol.Div. und 58. I.D. angewiesen worden.[…]15.11.1941:

[…]Einige Zivilisten, die sich der eigenen Linie nähern wollten, wurden erschossen. […]

Translation:Quote:

24.10.1941

The commanding general visited a number of firing positions of heavy and light batteries of artillery regiment 269. The commanding general viewed the installations for the winter and the construction of emplacements and then discussed with the commanders and battery leaders the use of the artillery in case of the Russian civilian population trying to break out of Leningrad. According to army order of 18.9.1941 Nr. 2737/41 secret, such attempts are to be prevented, if necessary by force of arms. It is the task of the artillery to fend off any such undertaking as far away as possible from our own lines by opening fire at an early stage, so that the infantry is as far as possible spared having to shoot on civilians.

The same instructions were given during troop visits in the last days to the artillery regiments of the SS Police Division and the 58th Infantry Division.[…]15.11.1941:

[…] Some civilians who were trying to get close to our own lines were shot. […]10. Study from the Army High Command 18/1a, War Diary No. 4a, entry of 4.11.1941 (State Archive Nuremberg, NOKW-1548)

Quote:

Möglichkeiten

für die Behandlung der Zivilbevölkerung von

Petersburg1.) Die Stadt bleibt abgeschlossen und alles verhungert.

2.) Die Zivilbevölkerung wird durch unsere Linien herausgelassen und in unser Hintergelände abgeschoben.

3.) Die Zivilbevölkerung wird durch einen Korridor hinter die russische Front abgeschobenDie Voraussetzung für diese 3 Punkte ist, daß die russische Wehrmacht, d.h. die Kräfte in Petersburg und die 8. Armee, möglichst auch die Besatzung von Kronstadt ausgeschaltet ist und zwar entweder durch Kapitulation oder durch Zusammenbruch und Auflösung.

Zu 1.):

Vorteile:

a.) Ein großer Teil der kommunistischen Bevölkerung Rußlands, die gerade unter der Bevölkerung von Petersburg zu suchen ist, wird damit ausgerottet.

b.) Wir brauchen 4 Millionen Menschen nicht zu ernähren.Nachteile:

a.) Seuchengefahr.

b.) Die seelische Einwirkung durch die vor unserer Front verhungernden Massen auf unsere Truppen ist groß.

c.) Der feindlichen Presse wird ein wirksames Propagandamittel in die Hand gegeben.

d.) Nachteilige Auswirkungen auf die innenpolitische Entwicklung hinter der russischen Front.

e.) Alle deutschen, finnischen und noch vorhandenen wertvollen russischen Elemente werden als erstes umkommen.

f.) Wir können keinerlei Material aus der Stadt herausholen, da wir nicht hineinkönnen.Vorbedingung:

a.) Eine starke Absperrung vor unserer Linie ist erforderlich.

b.) Der Ladogasee muß abgesperrt werden, sonst verhungert die Bevölkerung, vor allem aber die Truppe in Petersburg nicht.Zu 2.):

Vorteile:a.) Wir entlasten uns sowohl vor der Welt als auch vor unserem eigenen Volk dadurch, daß wir für die Bevölkerung Petersburgs das einzige in unsere Macht liegende tun.

b.) Der Weltpresse wird die Unterlage für die Propaganda zu einem großen Teil entzogen.

c.) Deutsche, finnische und noch vorhandene wertvolle russische Elemente können gerettet werden.Nachteile:

a.) Die Petersburger Bevölkerung fällt der Bevölkerung in unserem rückwärtigen Gebiet zur Last und beeinträchtigt damit auch unsere Ernährungslage.

b.) Seuchen können übertragen werden.

c.) Ein großer Teil der aus Petersburg herauskommenden wird auch so verhungern und es ergibt sich auch damit eine starke seelische Belastung für unsere Truppe.

d.) Ein großer Haufe kommunistischer Elemente ergießt sich in unser Hinterland. Damit Vermehrung der Partisanen und Aufhetzung der z.Zt. gutwilligen Landbevölkerung.

e.) Die wehrfähigen Männer werden wahrscheinlich auch in Kriegsgefangenschaft überführt werden müssen. Damit Vermehrung der zu Ernährenden.Vorbedingung:

a) Beim Herauslassen der Bevölkerung Untersuchung auf Waffen.

b) Geregelter Abschub nach hinten.Zu 3.):

Vorteile:

a.) Vermehrte Entlastung wie unter 2.)a.).

b.) Die Unterlage für die Weltpresse wird abgeschwächt wie unter 2.) b.).

c.) Unsere Truppe wird seelisch nicht so start beeindruckt wie bei Möglichkeit 2.).

d.) Wir werden die kommunistischen Elemente los.

e.) Die Ernährungslage im Hinterland wird dadurch nicht berührt.

f.) Man kann deutsche, finnische und vielleicht auch wertvolle russische Elemente herausziehen.

g.) Nehmen die Russen die Bevölkerung aus Petersburg nicht auf, so haben wir ein gutes Propagandamittel gegen die Sowjetregime in der Hand.Nachteile:

a.) Auf dem Marsch werden sehr viele Leute umkommen und die Feindpresse wird den ‘Hungermarsch’ propagandistisch ausschlachten.

b.) Für die ‘spalierbildende’ Truppe wird dieser Hungermarsch eine starke seelische Belastung.Vorbedingung:

a.) Die Russen müssen sich bereiterklären, die Bevölkerung aufzunehmen.

b.) Der Abmarsch muß erfolgen:

nördl. der Newa nach Schlüsselburg, dort über eine Pontonbrücke, dann längs des Ladogasees, sodaß möglichst wenig Kräfte für das ‘Spalier’ benötigt werden.

(con’t)08-10-2004, 07:05 AM

PotyondiTranslation:

Quote:

Possibilities

for the treatment of the civilian population of

Petersburg1.) The city remains encircled and all starve to death.

2.) The civilian population is let out through our lines and pushed away into our rear area.

3.) The civilian population is pushed off through a corridor behind the Russian frontThe pre-condition for these 3 points is that the Russian armed forces, i.e. the forces in Petersburg and the 8th Army, if possible also the garrison of Kronstadt, are eliminated either through capitulation or through collapse and dissolution.

Regarding 1.):

Advantage:

a.) A great part of the Communist population of Russia, which is to be found especially among the population of Petersburg, will thus be exterminated.

b.) We don’t have to feed 4 million people.Disadvantages:

a.) Danger of epidemics.

b.) The psychological effect of the masses starving to death before our front line on the troops is great.

c.) The enemy press is given an effective propaganda tool.

d.) Disadvantageous effects on the development of domestic policies behind the Russian front.

e.) All German, Finnish, German and still existing valuable Russian elements will be the first to perish.

f.) We can take no material out of the city because we cannot enter it.Pre-condition:

a.) A strong shut-off position in front of our line is necessary.

b.) Lake Ladoga must be sealed off, otherwise the population, but especially the troops in Petersburg will not starve.Regarding 2.):

Advantages:a.) We relieve ourselves both in front of the world and in front of our own people by doing for the population of Petersburg the only thing we are able to.

b.) The world press is to a great extent deprived of the basis for propaganda.

c.) German, Finnish and still existing valuable Russian elements can be saved.Disadvantages:

a.) The population of Petersburg is a burden for the population in our rear area and thus also affects our own food situation.

b.) Epidemics can be transmitted.

c.) A great part of those coming out of Petersburg will starve to death anyway and this will also lead to a strong psychological burden for our troops.

d.) A huge bunch of Communist elements will spread across our rear area. Thus increase of partisans and incitement of the at present good-willed population.

e.) The men able to fight will probably have to be led into captivity. This will increase the number of those to be fed.Pre-condition:

a) Search for weapons when letting out the population.

b) Orderly removal to the rear area.Regarding 3.):

Advantages:

a.) Increased relief as under 2.) a.).

b.) The basis for world press is weakened as under 2.) b.).

c.) Our troops are not so strongly affected psychologically as in possibility 2.).

d.) We get rid of the Communist elements.

e.) The food situation in the rear area is not affected hereby.

f.) German, Finnish and maybe also valuable Russian elements can be pulled out.

g.) If the Russians don’t take the people of Petersburg, we will have a good propaganda tool against the Soviet regime in our hands.Disadvantages:

a.) On the march a great many people will perish and the enemy press will take advantage of the ‘hunger march’ for propaganda purposes.

b.) For the ‘escorting’ troops this hunger march will be a strong psychological burden.Pre-condition:

a.) The Russians must declare themselves prepared to take the population.

b.) The marching off must be carried out:

North of the Neva towards Schlüsselburg, there across a pontoon bridge, then along Lake Ladoga, so that as few forces as possible are required for the ‘escort’.11. Notes of the Head of the General Staff of the 18th Army, Colonel Hasse, from the high level meeting at Orsha on 13.11.1941 (State Archive Nuremberg, NOKW-1535)

Quote:

Bericht über Ausführungen Wagners (Auszug):

[…]Unlösbar dagegen ist die Frage der Ernährung der Großstädte. Es kann keinem Zweifel unterliegen, daß insbesondere Leningrad verhungern muß, denn es ist unmöglich, diese Stadt zu ernähren. Aufgabe der Führung kann es nur sein, die Truppe hiervon und von den damit verbundenen Erscheinungen fern zu halten.[…]

Translation:Quote:

Report on Wagner’s statements (excerpt):

[…]The feeding of the great cities can however not be solved. There can be no doubt that especially Leningrad must starve to death, because it is impossible to feed this city. The task of the leadership can thus only be to keep the troops away from this and from the phenomena related hereto.[…]08-10-2004, 07:06 AM

PotyondiThe following three documents transcribed are reconnaissance reports on the situation inside Leningrad as a consequence of the German blockade.

12. Operational Situation Report (Ereignismeldung) UdSSR No. 154 of 12.1.1942 (Bundesarchiv, R 58/220)

Quote:

[…]Erkundung Petersburg,

Bevölkerung:

Die Bevölkerung Leningrads hat sich mittlerweile an den ständigen Artilleriebeschuss derart gewöhnt, dass kaum jemand die Schutzräume aufsucht. […] Die Verluste unter der Zivilbevölkerung sind demgemäss stark angestiegen. Trotzdem dürften die Verluste durch Artillerie und Bombeneinwirkung nach übereinstimmenden Schätzungen aufs Ganze gesehen gering sein und nur einige Tausend Personen betragen. Demgegenüber sollen in der letzten Zeit sich die Fälle von Hungertod beträchtlich vermehrt haben und in den letzten Wochen etwa das Vierfache der Verluste durch Artilleriebeschuss ausmachen. So wurde beispielsweise am 17. Dezember von einer Person auf der Statschekstrasse, zwischen Narwa-Tor und Stadtrand, also auf einer Strecke von 5 Kilometer beobachtet, dass allein 6 Personen entkräftet zusammenbrachen und liegenblieben. Diese Fälle häufen sich bereits derart, dass sich niemand mehr um die liegengebliebenen Personen kümmert, zumal bei der allgemeinen Entkräftung auch die Wenigsten in der Lage sind, tatkräftige Hilfe zu leisten. […]

Translation:Quote:

[…]Reconnaissance Petersburg,

Population:

The people of Leningrad has in the meantime become so used to the constant artillery bombardment that hardly anybody goes to the shelters. […] The losses among the civilian population have thus greatly increased. Nevertheless the losses from the effect of artillery and bombs should, according to coincident estimates, be low on the whole and amount to only several thousand persons. On the other hand the cases of death by starvation are said to have increased considerably in the last time and to have made up about four times the losses from artillery fire in the past weeks. So for instance on 17 December a person in the Statshek Street, between the Narva Gate and the city limits, saw 6 persons collapsing from exhaustion and lying where they fell over a distance of 5 kilometers. These cases are already increasing to such an extent that no one any longer takes care of the persons lying on the street, especially as due to the general exhaustion only very few are in conditions to provide effective help. […]13. Operational Situation Report (Ereignismeldung) UdSSR No. 170 of 18.2.1942 (Bundesarchiv, R 58/220)

Quote:

[…]Schon im Dezember wiesen große Teile der Zivilbevölkerung Leningrads Hungerschwellungen auf. Es passierte immer wieder, daß Personen auf den Strassen zusammenbrachen und tot liegen blieben. Im Laufe des Januar begann nun unter der Zivilbevölkerung ein regelrechtes Massensterben. Namentlich in den Abendstunden werden die Leichen auf Handschlitten aus den Häusern nach den Kirchhöfen gefahren, wo sie, wegen der Unmöglichkeit, den hartgefrorenen Boden aufzugraben, einfach in den Schnee geworfen werden. In der letzten Zeit sparen sich die Angehörigen meist die Mühe des Weges bis zum Friedhof und laden die Leichen schon unterwegs am Strassenrand ab. Ein Überläufer machte sich Ende Januar die Mühe, an einer verkehrsreichen Strasse in Leningrad am Nachmittag die vorübergeführten Handschlitten mit Leichen zu zählen und kam im Verlauf einer Stunde auf eine Zahl von 100. Vielfach werden Leichen auch schon in den Höfen und auf umfriedeten freien Plätzen gestapelt. Ein im Hof eines zerstörten Wohnblocks angelegter Leichenstapel war etwa 2 m hoch und 20 m lang. Vielfach werden die Leichen aber gar nicht erst aus den Wohnungen abtransportiert, sondern bloß in ungeheizte Räume gestellt. In den Luftschutzräumen findet man häufig Tote, für deren Abtransport nichts geschieht. Auch beispielsweise im Alexanderowskaja-Krankenhaus sind in den ungeheizten Räumen, Gängen und im Hofe 1 200 Leichen abgestellt. Schon Anfang Januar wurde die Zahl der täglichen Todesopfer des Hungers und der Kälte mit 2 — 3 000 angegeben. Ende Januar ging in Leningrad das Gerücht, daß täglich bereits an die 15 000 Menschen sterben und im Laufe der letzten 3 Monate bereits 200 000 Menschen Hungers gestorben seien. Auch diese Zahl ist im Verhältnis zur Gesamtbevölkerung nicht allzu hoch. Es ist aber zu berücksichtigen, daß sich die Todesopfer mit jeder Woche ungeheuer steigern werden, wenn die jetzigen Verhältnisse — Hunger und Kälte — bestehen bleiben. Die eingesparten Lebensmittelrationen auf die einzelnen verteilt sind jedoch ohne Bedeutung. In besonderem Maße sollen Kinder Opfer des Hungers werden, namentlich Kleinkinder, für die es keine Nahrung gibt. In der letzten Zeit soll zudem noch eine Pockenepidemie ausgebrochen sein, die außerdem noch unter den Kindern zahlreich Opfer fordert.[…]

Translation:Quote:

[…]Already in December a great part of the population showed hunger swellings. It happened again and again that persons broke down on the streets and lay there dead. In the course of January now there commenced a veritable mass dying among the population. Namely in the evening hours the corpses were drawn on hand sleds from the houses to the cemeteries, where due to impossibility of digging up the frozen ground they were simply thrown into the snow. Lately the relatives save themselves the effort of going to the cemetery and already unload the corpses on the way at the edge of the road. A defector undertook at the end of January to count the passing hand sleds with corpses on a traffic-rich street of Leningrad in the afternoon and counted 100 within an hour. In many cases the corpses were piled up in yards and on fenced-in free squares. A pile of corpses in the yard of a destroyed apartment block was about 2 meters high and 20 meters long. In many cases, however, the bodies are not even taken out of the apartments but only placed in unheated rooms. In the air raid shelters one often finds dead for whose removal nothing is done. Also for example in the Alexanderowskaja hospital there are about 1,200 corpses placed in the unheated rooms, aisles and in the yard. Already at the beginning of January the number of daily victims of starvation and cold was given at 2 – 3,000. At the end of January the rumor ran in Leningrad that already 15,000 people were dying every day and in the last 3 months 200,000 people had died of hunger. This number is not all too high in relation to the total population. It must be taken into account, however, that the number of dead will increase greatly with every week if the present conditions — hunger and cold – are maintained. The food rations saved and distributed to individuals have no influence.

Especially children are said to become victims of the hunger, namely small children for whom there is no food. Lately also a smallpox epidemic is said to have broken out, which additionally claimed many victims among the children.[…]14. Operational Situation Report (Ereignismeldung) UdSSR No. 191 of 10.4.1942 (Bundesarchiv, R 58/221)

Quote:

[…] In gesteigertem Masse wurde die Verbindungsstrasse über das Eis des Ladoga-Sees von den Leningrader Behörden auch weiterhin nicht nur zur Heranschaffung von Kriegsmaterial und Lebensmitteln, sondern in gesteigerten Masse auch zur Evakuierung eines Teils der Bevölkerung nach dem Innern der Sowjetunion benutzt.[…]

Umfangmässig weit bedeutender als der Abzug über den Ladogasee ist die Verminderung der Leningrader Bevölkerung durch das unverändert anhaltende Massensterben. Die angegebenen Zahlen der täglichen Todesfälle schwanken, liegen aber durchweg über 8 000. Die Todesursachen sind Hunger, Erschöpfung, Herzschwäche und Darmkrankheiten.[…]

Translation:Quote:

[…] The road across the ice of Lake Ladoga continues to be used by the Leningrad authorities not only to bring in war material and food, but increasingly also to evacuate a part of the population to the inner Soviet Union.[…]

Much more important in terms of numbers than the evacuation across Lake Ladoga is the reduction of the population of Leningrad due to the mass dying that continues to occur without a change. The indicated numbers of daily deaths vary, but always lie above 8,000. The causes of death are hunger, exhaustion, heart failure and intestine diseases.[…]08-10-2004, 07:07 AM

PotyondiThe following quotes are from:

Harrison E. Salisbury, The 900 Days. The Siege of Leningrad. Avon Books, New York, 1970

Page 383

Quote:

[…]Hitler insisted that von Leeb draw the tightest kind of circle around Leningrad. Secretly, the Führer instructed von Leeb that the city’s capitulation was not to be accepted. The population was to die with the doomed city. Random shelling of civilian objectives was authorized. If the populace tried to escape the iron ring, they were to be shot down.

No hint of this brutal decision was made public.[…]

Pages 468 and followingQuote:

On December 8 [1941] Meretskov’s Fourth Army fought into Tikhvin. By December 9 the city was firmly in Soviet hands again. It had been held by the Germans precisely one month. Its recapture on the seventieth day of the siege was the first real sign that the lines around Leningrad could be held, that the second ring could not be fastened about the northern capital, that the Nazi dream of striking to the east of Vologda and cutting off Moscow from the rear, from Siberia, from America, would be thwarted.

It coincided with a directive signed by Hitler December 8, No. 59, in which he ordered Army Group North to strengthen its control of the railroad and highway from Tikhvin and Volkhov to Kolchanovo in order to secure the possibility of joining hands with the Finns in Karelia.

Tikhvin was a real victory. Whether it would save Leningrad and its millions of people, now entering the skeletal world of starvation, of life without heat, without light, without transport, no one knew for certain.

[…]

The Germans did not think so. Colonel General Halder, the diarist of the Wehrmacht, jotted down under the date of December 13: “The Commander of the army group is inclined to the view – after the failure of all attempts by the enemy to liquidate our foothold on the Neva – that we may expect the complete starvation of Leningrad.”

Pages 483 and followingQuote:

To give the starving, freezing people hope to help them to survive the New Year and the recapture of Mga, hundreds of meetings were held throughout the city – in the ice-festooned factories (hardly a plant was operating now – on December 19, 184 plants had been put on a one-, two- or three-day week); in the windowless government offices; in the apartment houses where burned small burzhuiki –makeshift stoves. The word was passed on to all: by January 1 Leningrad will be liberated; the circle will be broken; Mga will be retaken.

But Mga was not retaken. Even before New Year’s Day it was suddenly plain to Zhdanov that his Christmas optimism had been ill-founded. The terrible truth was that the Soviet troops had neither the physical strength nor the munitions to dislodge the Nazis.

The Red Army men were weak and sick. A report as of January 10 showed 45 percent of the units of the Leningrad front and 63 percent of the Fifty-fifth Army units understrength. There were 32 divisions on the front. Of these, 14 were only up to 30 percent of strength. Some infantry regiments were only at 17 to 21 percent of authorized manpower.

Now was there any way to bolster their ranks. […]

These replacements hardly matched the Red Army’s losses. From October, 1941 to April, 1942, 353,424 troops reported sick or wounded, an average of 50,000 a month or 1,700 a day. Half of these were ill, largely of dystrophy and other starvation ailments. More than 62,000 troops came down with dystrophy from November, 1941, to the end of spring. The number ill with scurvy reached 20,000 in April, 1942. Deaths due to starvation diseases were 12,416, nearly 20 percent of troops on sick call, in the winter of 1942.

Pages 555 and followingQuote:

[…]On Nakhimson Prospekt Luknitsky found his sled colliding with those of others passing him with corpses. One was a sled on which there were two corpses, the body of a woman with long hair trailing in the snow and that of a small girl, probably ten years old. He passed carefully in order to avoid tangling the whitish-yellow hair of the corpse with the runner of his sled.

On the Volodarsky near the Liteiny Bridge he encountered a five-ton truck with a mountain of bodies. Farther on he met two old women who were conveying their corpses to the cemetery in style. They had hitched their sleds to an army sledge which was slowly pulled through the streets by a pair of starving horses. There he met the shadow of a man who carried nestled to his breast and incredibly thin dog – one of the rarest of city sights. The eyes of both the man and the dog were filled with hunger and terror, the dog’s terror, no doubt, because he sensed his fate and the man’s, perhaps, because he feared someone might rob him of the dog and he would not have the strength to defend his possession.

So Luknitsky walked through the city, passing hundreds of people, struggling to survive, pulling the corpses of their relatives towards hospitals and cemeteries, pulling their little sleds bearing pails of water.

Among the hundreds he met another kind as well – a man with a fat, self-satisfied face, well-fed, with greedy eyes. Who was this man? Possibly, a store worker, a speculator, an apartment house manager who stole the ration cards of the tenants as they died and with the aid of his mistress exchanged the miserable bread rations in the Haymarket for gold watches, for rich silks, for diamonds or old silver and golden rubles. The conversation of this man and his mistress would not be of survival, of how to live through their terrible times. On such things this man would merely spit. Was he a speculator? A murderer? A cannibal? There was little difference; each was trading on the lives of starving, dying people, each was living on the flesh of his fellows.

For such persons there was only one recourse. They must be shot.

Luknitsky met Red Army men, too. They were as thin and weak as the civilians. He passed two soldiers, half-carrying a third. Most of them, despite their weakness, tried to walk with a bold step.[…]

Pages 590 and followingQuote:

On Aril 15 [1942] Leningrad marked the 248th day of siege. The city had survived. But the cost had no equal in modern times. In March the Leningrad Funeral Trust buried 89,968 persons. In April the total rose to 102,497. Some of these burials were due to clean-up, but the death rate was probably higher in April than in any other month of the blockade.

There now remained in Leningrad, with evacuation at an end, 1,100,000 persons. The total of ration cards was 800,000 less than in January. When Leningrad’s supply resources — the 58 days of flour, the 140 days of meat and fish — were calculated, it was on the basis of a population on April 15 only one-third of what it had been when the blockade began August 30 with the loss of Mga.

More people had died in the Leningrad blockade than had ever died in a modern city — anywhere — anytime: more than ten times the number who died in Hiroshima.

(Footnote: Deaths at Hiroshima August 6, 1945, were 78,150, with 13,983 missing and 37,426 wounded. In another tragedy of World War II, the Warsaw uprising, between 56,000 and 60,000 died.)

By comparison with the great sieges of the past Leningrad was unique. The siege of Paris had lasted only 121 days, from September 19, 1870 to January 27, 1871. The total population, military and civilian, was on the order of one million. Noncombatant deaths from all causes in Paris during November, December and three weeks of January were only 30,236, about 16,000 higher than in the comparable period of the preceding year. The Parisians ate horses, mules, cats, dogs and possibly rats. There was a raid on the Paris zoo and a rhinoceros was killed and butchered. There were no authenticated instances of cannibalism. Food was scarce, but whine was plentiful.

In the great American siege, that of Vicksburg between May 18 and July 4, 1863, only 4,000 civilians were involved, although the Confederate military force was upwards of 30,000. About 2,500 persons were killed in the siege, including 119 women and children. No known deaths from starvation occurred. Horses, mules, dogs and kittens were eaten and possibly rats.

Leningrad exceeded the total Paris civil casualties on any two or three winter days. The Vicksburg casualties, military and civil, were exceeded in Leningrad by starvation deaths on any January, February, March or April day.

How many people died in the Leningrad blockade? Even with careful calculation the total may be inexact by several hundred thousand.

The most honest declaration was an official Soviet response to a Swedish official inquiry published in Red Star, the Soviet Army newspaper, June 28, 1964, which said: “No one knows exactly how many people died in Leningrad and the Leningrad area.”

The official figure announced by the Soviet government of deaths by starvation — civilian deaths by hunger in the city of Leningrad alone — was 632,253. An additional 16,747 persons were listed as killed by bombs and shells, providing a total of Leningrad civilian deaths of 649,000. To this were added deaths in nearby Pushkin and Peterhof, bringing the total of starvation deaths to 641,803 and of deaths from all war causes to 671,635. These figures were attested to by the Leningrad City Commission to Investigate Nazi Atrocities and were submitted at the Nuremberg Trials in 1946.

The Commission figures are incomplete in many respects. They do not cover many Leningrad areas, including Oranienburg, Sestroretsk and the suburban parts of the blockade zone. Soviet sources no longer regard the Commission totals, which apparently were drawn up in May, 1944, as authoritative, although they were prepared by an elaborate apparatus of City and Regional Party officials, headed by Party Secretary Kuznetsov. A total of 6,445 local commissions carried out the task, and more than 31,000 persons took part. Individual lists of deaths were made up for each region. The regional lists carried 440,826 names, and a general city-wide list added 191,427 names, providing the basic Commission-reported total of 632,253.

Impressive evidence has been compiled by Soviet scholars to demonstrate the incompleteness of the Commission’s total. All official Leningrad statistics are necessarily inaccurate because of the terrible conditions of the winter of 1941-42. The official report of deaths for December, 53,000, may be fairly complete, but for January and February the figures are admittedly poor. Estimates of daily deaths in these months run from 3,500 to 4,000 a day to 8,000. The only total available gives deaths for the period as 199,187. This is offered by Dimitri Pavlov. It represents deaths officially reported to authorities (probably in connection with the turning in of ration cards of the deceased). The number of unregistered deaths is known to be much higher. The Funeral Trust buried 89,968 bodies in March (it has no records for January and February), 102,497 in April and 53,562 in May. It continued to bury 4,000 to 5,000 bodies a month through the autumn of 1942, although by this time Leningrad’s population had been cut by more than 75 percent. Thus mortality as a result of the blockade and starvation continued at a high rate through the whole year.

The Funeral Trust buried 460,000 bodies from November, 1941, to the end of 1942. In addition, it is estimated that private individuals, work teams of soldiers and others transported 228,263 bodies from morgues to cemeteries from December, 1941 through December, 1942.

No exact accounting of bodies delivered to cemeteries was possible in Leningrad during the winter months, when thousands of corpses lay in the streets and were picked up like cordwood, transported to Piskarevsky, Volkov, Tatar, Bolshaya Okhta, Serafimov, and Bogoslovsky cemeteries and to the larger squares at Vesely Poselok (Jolly Village) and the Glinozemsky Zavod for burial in mass graves, dynamited in the frozen earth by miliary miners.

Leningrad had a civilian population of about 2,280,000 in January, 1942. By the close of evacuation via the ice road in April, 1942, the population was estimated at 1,100,000 — a reduction of 1,180,000, of whom 440,000 had been evacuated via the ice road. Another 120,000 went to the front or were evacuated in May and June. This would indicate a minimum of deaths within the city of about 620,000 in the first half of 1942. Official statistics show that about 1,093,695 persons were buried and about 110,000 cremated from July, 1941, through July, 1942.

To take another approach, Leningrad had about 2,500,000 residents at the start of the blockade, including about 100,000 refugees. At the end of 1943 as the 900 days were drawing to a close, Leningrad had a population of about 600,000 — less than a quarter the number of residents at the time Mga fell August 30, 1941.

The most careful calculation suggests that about 1,000,000 Leningraders were evacuated during the blockade: 33,479 by water across Ladoga in the fall of 1941; 35,114 by plane in November-December, 1941; 36,118 by the Ladoga ice road in December, 1941, and up to January 22, 1942; 440,000 by Ladoga from January 22 to April 15; 448,694 by Ladoga water transport from May to November, 1942; 15,000 during 1943. In addition, perhaps 100,000 Lenigraders went to the front with the armed forces.

This suggests that not less than 800,000 persons died of starvation within Leningrad during the blockade.

But the 800,000 total does not include the thousands who died in the suburban regions and during evacuation. These totals were very large. For instance, at the tiny little station of Borisova Griva on Ladoga 2,200 persons died from January to April 15, 1942. The Leningrad Encyclopedia estimates deaths during evacuation at “tens of thousands”.